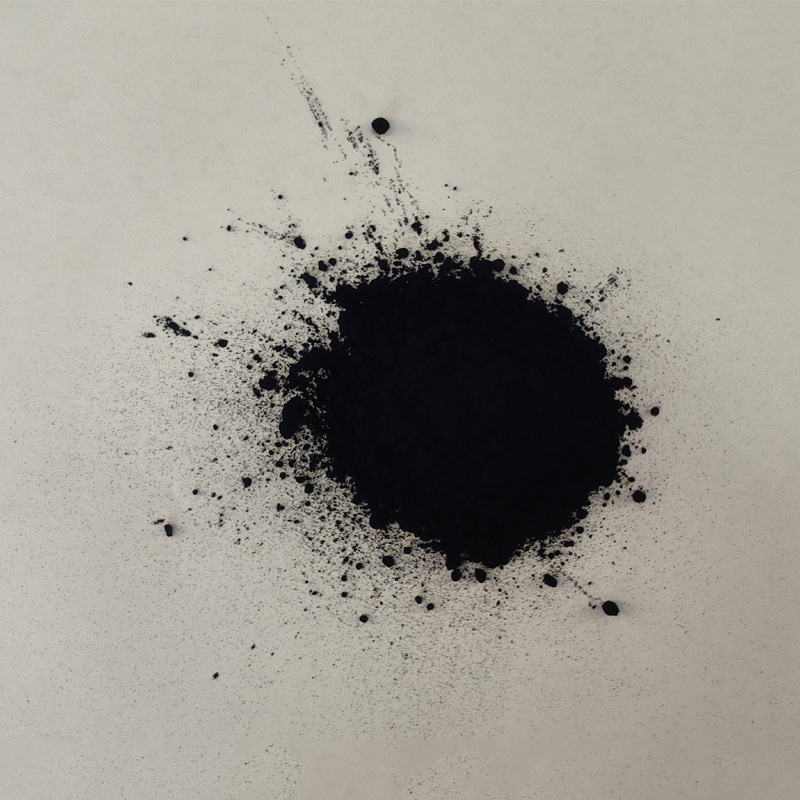

Natural indigo is extracted from the leaves of indigofera tinctoria, a short shrub that is a member of the legume family. Indigo is now cultivated world-wide, but is probably native to South Asia (Glowacki et al. 2012:542). It has been the most important source of blue dye for much of recorded history, and there is archaeological evidence that indigo was being used to dye fabric up to 4,000 years ago in India. Natural indigo was a major global commodity in the 18th and 19th centuries, and industries sprang up all across the world. It was one of the major exports of the antebellum U.S. South, especially around low-country South Carolina and Georgia, which have subtropical climates ideal for growing indigo. However, a German chemist identified the chemical structure of indigotin and discovered how to synthesize it in 1883 (ibid:542). This lead to the collapse of the indigo-growing industry. Today indigo is still the most important blue dye for clothing and jeans, but almost all of it is synthetically produced indigo, not indigo extracted from a plant.

Indigo is unique among all natural dyes in how it attaches to fiber. Boiling it in hot water will have no effect, because the blue coloring compound indigotin is insoluble in normal water. The traditional method of applying it involves fermenting the leaves, extracting the dyestuff, dissolving it in a reduction vat, and then dipping fabric in the vat. When fabric is removed from the vat, the dissolved indigotin oxidizes and comes back out of solution, bonding immediately to the fiber. However, it is possible to short-circuit this laborious process by taking advantage of the chemistry of indigo leaves.

Indigo does not exist in the plant in the form of blue indigotin—otherwise the plant itself would be blue. Instead, it exists in the form of two precursors, beta-glucosidase and indican. If the leaf is damaged by grazing herbivores or gnawed by insects, the precursors are mixed together and blue indigotin forms. This may have evolved as a defense mechanism against predation, although the evidence is unclear (Daykin 2011:5). If high-quality indigo leaves are harvested very carefully, the two precursors are preserved even after the leaves are dried. They can later be blended with ice water to mix the precursor compounds and begin the chemical reaction leading to blue indigotin. As the cold water warms up, the beta-glucosidase cleaves the indican into a molecule of indoxyl, and the indoxyl reacts with oxygen dissolved in the water to form blue indigotin. Any wool or silk soaking in the water while this reaction occurs will be dyed blue, too. Using fresh indigo leaves it is possible to achieve beautiful shades of turquoise and ice blue, without needing to build a reduction vat.

Nature’s Strongest Blue

2. Safety Precautions

-

DO NOT INGEST. This product is intended for textile dyeing, not as an herbal supplement.

-

Avoid eye contact. If eye contact occurs, rinse with cool water.

-

Not for use as a cosmetic additive; do not apply directly to skin or hair.

-

If a spill occurs, quickly wipe up with a paper towel or disposable rag.

-

Use only dye pots and utensils dedicated to dyeing. Do not use any pots, containers, spoons, tongs, thermometers, or other utensils that will be used for food preparation.

-

Dried indigo leaf, and all dye baths and mordant liquors made while dyeing, should be kept out of reach of children and pets. Use only with adult supervision.