Is Natural Indigo More Sustainable than Synthetic?

Let’s Settle the Matter: Is Natural Plant-Based Indigo Dye More Sustainable Than Synthetic Indigo?

Continuing our series of mythbusting and clarifying, we now turn our eye toward another essential ingredient for denim: indigo dye.

Conscious consumers have a tendency to romanticize the natural stuff that is produced from plants, swooning over its long history of use in traditional and artisan fashion production, while turning up their noses (in theory) at modern synthetic dyes that make churning out millions of $20 fast fashion jeans possible.

But is that sustainable snobbery warranted when it comes to indigo dye? The story of plant-based versus synthetic indigo is a little more complex than that… it’s not so blue and white. (Sorry, we had to.)

Let’s take a closer look at humanity’s favorite blue pigment and find out once and for all: Is plant-based natural indigo superior to fossil-fuel based indigo? And if it is, would it even be possible to bring it back?

The Dark History of Natural Indigo

Plant indigo has been in use since at least the fourth millennium BC, according to an old piece of dyed cotton cloth found in Peru. As Jenny Balfour-Paul writes in her authoritative and sweeping book Indigo: Egyptian Mummies to Blue Jeans, it has a story as rich (and problematic) as any other prized commodity such as silk, tea, cotton, coffee or sugar. It drove trade for more than a millennium, has been worn by kings, peasants and “blue collar” workers alike, and encouraged the colonization of the Global South.

There are several different types of plants that bear indigo and they grow all over the world, from subtropical to temperate climates in Europe, Africa, Asia and the Americas. Indican, the chemical source of the indigo dye, is the same no matter which of these plants it comes from, whether indigofera from India, Africa or Central America; woad from Europe; or polygonum tinctorium from Japan. But of course, it was more profitable to grow it in the colonies, where labor was cheap, or even free, due to slavery.

Compared to other dyes, indigo is exceedingly complex in chemistry and application. It can take up to two weeks to prepare and ferment a finicky vat of natural indigo dye. “It’s a long process and is very tough and requires a lot of hard work to take the indigo out of the plants,” says Miguel Sanchez, a textile chemistry expert and Technology Leader at Kingpins. Despite being viewed as a rare skill and art, akin to magic, making natural indigo was dirty, difficult and exceedingly smelly—urine was often added for the required fermenting process.

Pure, natural indigo has been traditionally used topically for a wide variety of ailments, renowned for its “antiseptic, astringent and purgative qualities,’ Balfour-Paul writes. But it is toxic if ingested in large enough amounts. British overseers forced Indian workers to wade into foul-smelling fermenting vats, which, according to Diderot’s Encyclopédie, ‘killed many workers.’ Balfour-Paul continues, “Local populations were understandably reluctant to undertake a job said to cause, if not death itself, at least cancer, impotence, headaches and temporary lameness.”

Indigo plantations in the Americas, especially in South Carolina and the French West Indies, relied on slave labor for their profits, and British planters ruthlessly exploited the labor of low-caste Indians to work their indigo plantations. Gandhi’s first foray into civil disobedience was on behalf of Indian indigo peasants and some historians believe the decline of the indigo trade in Central America catalyzed the revolution against Spain. The abolition of slavery after the Civil War ended indigo’s production in the U.S. and speak volumes of the type of labor required to produce it.

With the US out of the market, Indian plantations dominated the supply. That is, until synthetic indigo was invented at the end of the century.

What’s the Difference Between Natural and Synthetic Indigo?

Chemically, synthetic indigo and natural indigo dye are exactly the same. Until recently, when a test was developed to identify whether the carbon in a material comes from fossil fuels, chemists were unable to distinguish the two. And it’s not uncommon to find out that someone claiming to sell natural indigo dye is actually selling the much cheaper and easier to obtain synthetic version.

Technically, their color is exactly the same as well, though natural indigo can contain impurities like indirubin, tannins and yellow flavonoids, which some believe make its color richer and interesting. “Natural indigo has less yield than synthetic indigo because it is less pure,” Sanchez says. “And the shade is duller compared to synthetic indigo again because of impurities.”

But the dye process is the same. “Once we get it into our facility, it’s dyed the same way as a synthetic indigo,” says Cone Denim president Steve Maggard of natural indigo dye. “Same machinery, same processes, same auxiliary chemicals in a lot of cases.”

Most other natural dyes—plant, insect, and mineral—require another kind of chemical, broadly called mordants, to make them bond with textiles. Indigo (natural and synthetic) works differently. It’s a pigment instead of a dye, without affinity for fibers. To make it soluble, a reducing agent, sodium hydrosulphite in modern times, has to be added.

“It breaks the molecule of Indigo in a way that it has a little bit of solubility. And it has a little bit of affinity for the fabric, not much but a little bit,” says Sanchez. “The dye is very lazy. You cannot put a lot of indigo in one go on the yarn. You have to apply it like you’re painting, one by one layer by layer.”

You dip a textile in the yellow indigo vat, expose it to the air so it turns from yellow to blue, and then dip and fix it again, up to 12 times depending on the depth of blue you want. This deposits microscopic particles directly on the surface of textiles and threads, whereas normal dyes soak completely through the threads.

This layering, also called “ring dyeing,” is why with heavy use (or distressing done at the factory), indigo rubs off of denim and exposes the white of the underlying cotton.

The two World Wars temporarily stymied synthetic indigo’s takeover of the fashion world, but after World War II, plant-based indigo became a dye used only by indigenous villages and hobbyists. Many cities whose planter and merchant classes grew wealthy on indigo exported their last batch sometime in the 1970s and 80s.

In fact, it looked as though the fashion industry was going to give up on synthetic indigo as well and switch to other simpler synthetic blue dyes, until blue jeans became a wardrobe staple in the 1960s. You simply cannot get this fading effect with other blue dyes.

How Toxic is Synthetic Indigo Dye?

There are several processes to produce synthetic indigo, but only one is used now because it gives the highest output for the lowest cost. “It requires special conditions and chemicals that you need to handle with extreme care,” Sanchez says. The chemicals involved include aniline, formaldehyde, hydrogen cyanide, and sodium amide (which can explode if it comes in contact with oxygen in the air or water). “This can happen in all chemical industries, but in the case of indigo, because of the type of chemicals that they are using, I mean, if there is any problem, it’s going to be bad,” Sanchez says.

For a time, synthetic indigo was produced in the US, but because of increasing environmental regulations, production started to shrink. As late as 1997, the Buffalo Color Corp in New York remained, producing 3,500 tons of synthetic indigo a year. But Chinese producers illegally dumped synthetic indigo on the US market at below cost in the late ‘90s and early 2000s until the Buffalo plant was forced to close in 2003. It was designated a Superfund site, due to the toxic runoff from production. The remaining buildings are full of hazardous blue dust and signs warning of the toxic ingredients used to make synthetic indigo.

“The manufacture of the raw materials of synthetic indigo from toxic chemicals such as aniline and cyanide pollutes rivers of China,” Balfour-Paul wrote by email. Like many things related to fashion, the process of manufacturing synthetic indigo in China is highly secretive. “No one is allowed in the factory that makes more than 50 percent of the world’s indigo in Inner Mongolia [in China],” alleges Sarah Bellos, Founder and CEO of the plant indigo startup Stony Creek Colors in Tennessee.

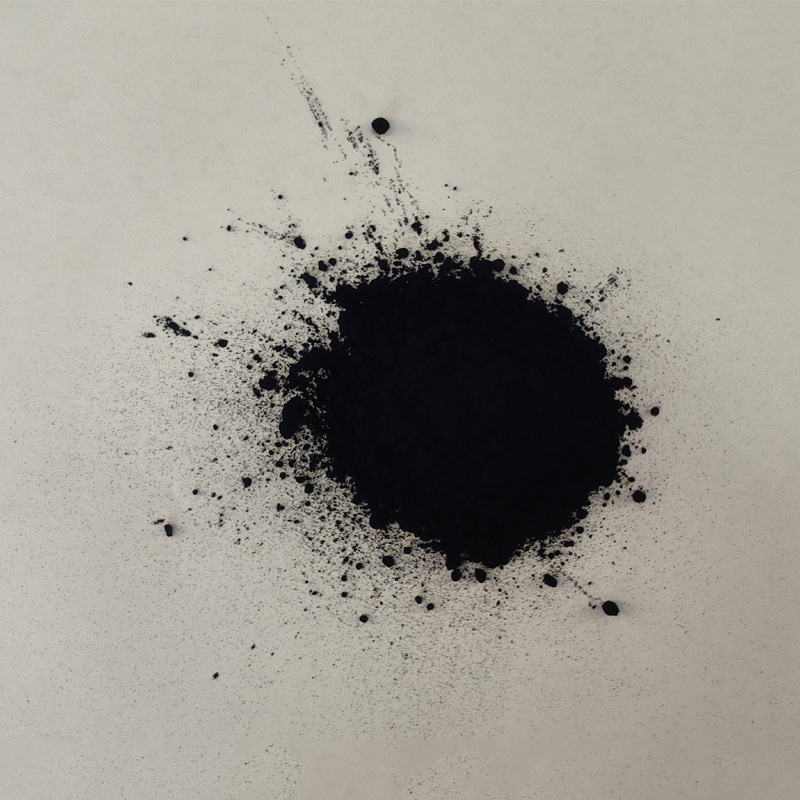

The conventional industrial production of synthetic indigo, which is the majority of production around the world and dominates Chinese production, creates a concentrated blue powder that is sold to denim dyeing facilities. When workers cut open sacks of indigo powder, creating “indigo bombs,” they can and do breathe in high amounts of carcinogenic aniline, among other substances. “It’s not good to breathe in, to touch, or to immerse your hands into indigo solutions, or to touch indigo granules with your bare hands,” Sanchez says. “Don’t do it. Or breathing in indigo dust. That’s bad.”

Further, when the dye houses combine it with a reducing agent, sodium hydrosulphite, it produces an equal amount of indigo and salt. Salt in small amounts is just fine, of course. But when it comes to 70,000 metric tons of it produced worldwide, it is a potent pollutant that is nearly impossible to dispose of responsibly. It can’t be taken out of water treatment except through reverse osmosis.

Even what you can buy at Amazon or Walmart is toxic. The synthetic indigo dye kits come with the reducing agent thiourea dioxide, which is better than sodium hydrosulphite, which would catch fire if you dropped water on it. But Thiox, as it’s often labeled, can be dangerous for your health and you must do your indigo dying in an extremely well ventilated area.

However, the German company DyStar, which produces 30 percent of the world’s synthetic indigo, is transparent about how it makes its synthetic indigo product. According to Sarah Bellos, nine percent of global indigo production is made in DyStar’s Germany facility. The process there was described to me by the Dystar team as a closed-loop, where the ingredients and byproducts are piped safely throughout the BASF industrial park for use in other manufacturing processes. The rest of DyStar’s production is in Brazil, India and China. More importantly, DyStar produces only a pre-reduced liquid indigo dye, which shields workers from toxic powder exposure and reduces the amount of waste salt by 70 percent.

DyStar has also developed another process which eliminates the use of sodium hydrosulphite completely in favor of an organic and biodegradable reducing agent. The resulting wastewater is much easier to treat. A two-year-old technology, it’s being used by some mills in Pakistan, Turkey and is being tested by Cone Denim.

Unfortunately, there is no way to tell as a consumer which type of indigo was used on your jeans unless the brand chooses to provide this information.

Should You Be Worried About Toxic Aniline on the Jeans That You Buy?

In the past decade, some consumers and industry folk have grown concerned about the carcinogenic substance aniline and its toxicity not just for garment workers, but consumers who buy and wear denim.

And it can be somewhat confusing to talk about aniline in relation to indigo. Añil is indigo’s Spanish and Portuguese name. Because aniline, a carcinogenic substance, was first obtained from indigo, it was given a name that relates it to indigo.

Aniline is used to create synthetic indigo, but it’s not used to process plant indigo nor is it present in plant-based indigo dye or products dyed with plant-based indigo. In that sense, modern natural indigo production is safer and less toxic for workers and the environment, as long as it is properly handled.

Traces of aniline can also show up if indigo on denim is burned by lasers in the distressing process. But overall, experts are not particularly concerned about the amount of aniline on your jeans, whether dyed with plant or synthetic indigo.

“The amount of aniline that is left on the article is below [safe] limits,” Sanchez says, as specified by the two safe chemistry certifications OEKO-TEX and GOTS. And dye companies certify that as long as the denim factory follows the technical directions, the final garment will be within limits.

How Can We Get Fossil Fuels Out of Indigo Dye?

Like almost all manmade dyes and chemicals, synthetic indigo’s base ingredients are derived from petroleum. But work has been done to develop bio-based manmade indigo. Korean scientists recently discovered a way to make indigo from bacteria, and a biotech startup called Huue in California has developed a process to create dye using microbes. It has been preparing to test its product but hasn’t publicly confirmed a timeline.

“The problem with bio-based technologies, again, is the scalability,” Sanchez says. “But it will be easier to scale up a biotechnology than a pure natural source.”

It may not be easy to scale natural indigo back up, but Stony Creek Colors in Tennessee is trying. The indigo dye maker, which works with local farmers to swap their tobacco crop out for indigo-producing plants which it then processes into dye, is the plant-based indigo supplier to Cone Denim’s North Carolina facility. Stony Creek indigo has been used by brands like Levi’s, Patagonia, Nudie Jeans, Lucky Brand, Wrangler and Taylor Stitch.

“You can get plant-based Indigo from other parts of the globe,” says Cone Denim president Steve Maggard. “But I think it’s a story that our U.S. retail customers like to tell. They’re supporting U.S. farmers and U.S. agriculture.”

But it’s still a niche product, comprising only 2 or 3 percent of the Cone facility’s annual indigo consumption. “Natural indigo has a very small market niche,” Sanchez says. “It’s only for capsule collections. If I am a person that really wants to do things in a less environmentally stressful way, I will probably go for natural. But we have to make some sacrifices.”

It mainly comes down to the cost. Synthetic indigo at a 94 percent concentration goes for around $6 per kilo, while natural indigo at a 20 percent concentration is around $120 per kilo. That’s a big difference for the notoriously price-conscious denim industry.

“If you’re buying, you know, a $3.50 a yard product, and then you switch to a natural indigo and it’s $5, that’s a significant price increase,” says Maggard. “Most of your larger mass market customers can’t pass along that price increase to their consumers. Where we’ve had success is with some smaller brands that have higher price points.”

Sarah Bellos, CEO and Founder of Stony Creek Colors, says the high price is due to the capital-intensive process of building Stony Creek’s operations over the past 10 years. “We’ve grown really slowly in terms of production, in order to work out all these really, really hard things, which are the entire agricultural value chain around plant-based indigo,” Bellos says.

A breeding team has worked on selecting a high-yield, consistent, and regenerative version of Indigofera suffruticosa, a tropical legume native to the Americas, and Stony Creek Colors pays farmers more per acre than what they would get for competitive crops. They’ve also developed new chemistries and a mechanical way of processing the plant that is far less labor intensive. Soon, hopefully, Stony Creek can kick into growth mode and economies of scale will bring down the price.

“If you come to our factory, it looks almost more like a brewery,” she says. “There’s tanks and pumps and valves. We’re making it like you would make other industrial products.”

The other drawback to natural plant indigo is the natural variation in the color. “The only way to obtain a consistent quality of natural indigo is by producing a lot of batches and combining them,” Sanchez says. “This is what Stoney Creek is doing.”

“It requires a little bit more time and hand holding just because you have to take into account the natural variation that can come in from crop to crop,” says Cone president Maggard. “You can’t just plug in the same formula you use the prior year and expect to have the same result. Once we get a crop, we are successfully able to dye it and make it consistent. But we’ve told our customers that there could be some variation.”

“There’s definitely disadvantages for the mill in switching [to plant-based indigo], because they have to literally switch out their tanks and stuff like that,” Bellos says. But she says Stony Creek will launch a major innovation to ease that problem in the next year.

The other huge roadblock is the land use required. About 25 to 85 pounds of pure pigment can be produced per acre. To satisfy the appetite of the global fashion industry—70,000 metric tons of pure indigo a year—many believe it would require way too much land. Estimates range from 2 to 10 million acres. For comparison, a little over 12 million acres of cotton, fashion’s most in-demand crop, were planted in the U.S. in 2020.

“I think that that’s just not true at all,” Bellos says of the land limitation. “To serve the entire denim industry is actually possible.” She says the plant they’ve bred can be used as a rotational cash crop and so wouldn’t compete with food crops and would actually benefit farmers and the soil. She wouldn’t share the expected yield of the plant Stony Creek has bred, for competitive reasons, but she says the yield will be higher than traditional indigo plants.

“We believe in a future where indigo should be part of a farmer’s rotation if they want it to be. They can plug in to the supporting infrastructure on each side, which is being able to get the plant and high-yielding genetics, but then also being able to process it and have someone else take it to market. And our model is 100 percent, scalable, even globally. We’re already breeding seeds for more tropical locations.”

“It is true indeed about the rotational aspect (and the brilliance of the Indigoferas as soil enrichers) and it intercrops very well with such crops as rice,” Balfour-Paul wrote by email. “So in theory Sarah could be correct. I hope she is, it’s a great aspiration.”

Cone president Maggard feels optimistic about the future of natural indigo, looking to organic food as an example of a consumer-driven shift toward sustainability. He also likes the story of giving former tobacco farmers something to switch to.

“It could appeal to brands that want a more authentic story,” Bellos says, “In terms of actually being able to understand and see where this really important chemical—a chemical that we need to make jeans—is coming from. Being able to put not just the farmer’s face, but a factory face, on the product. Understanding how this important resource is processed in a way that’s safe for workers, good for the environment, good for the community in which it’s made and is not this shadowy world of petrochemical manufacturing.”

“I am from the generation that treasured our fading, well-worn jeans and we were right about this without knowing then about the big role fast fashion would play in damaging the planet,” Balfour-Paul wrote. “However, we didn’t have the choice to buy naturally dyed jeans back then; now that choice is coming, it should be shouted from the rooftops.”