What is indigo?

What is indigo?

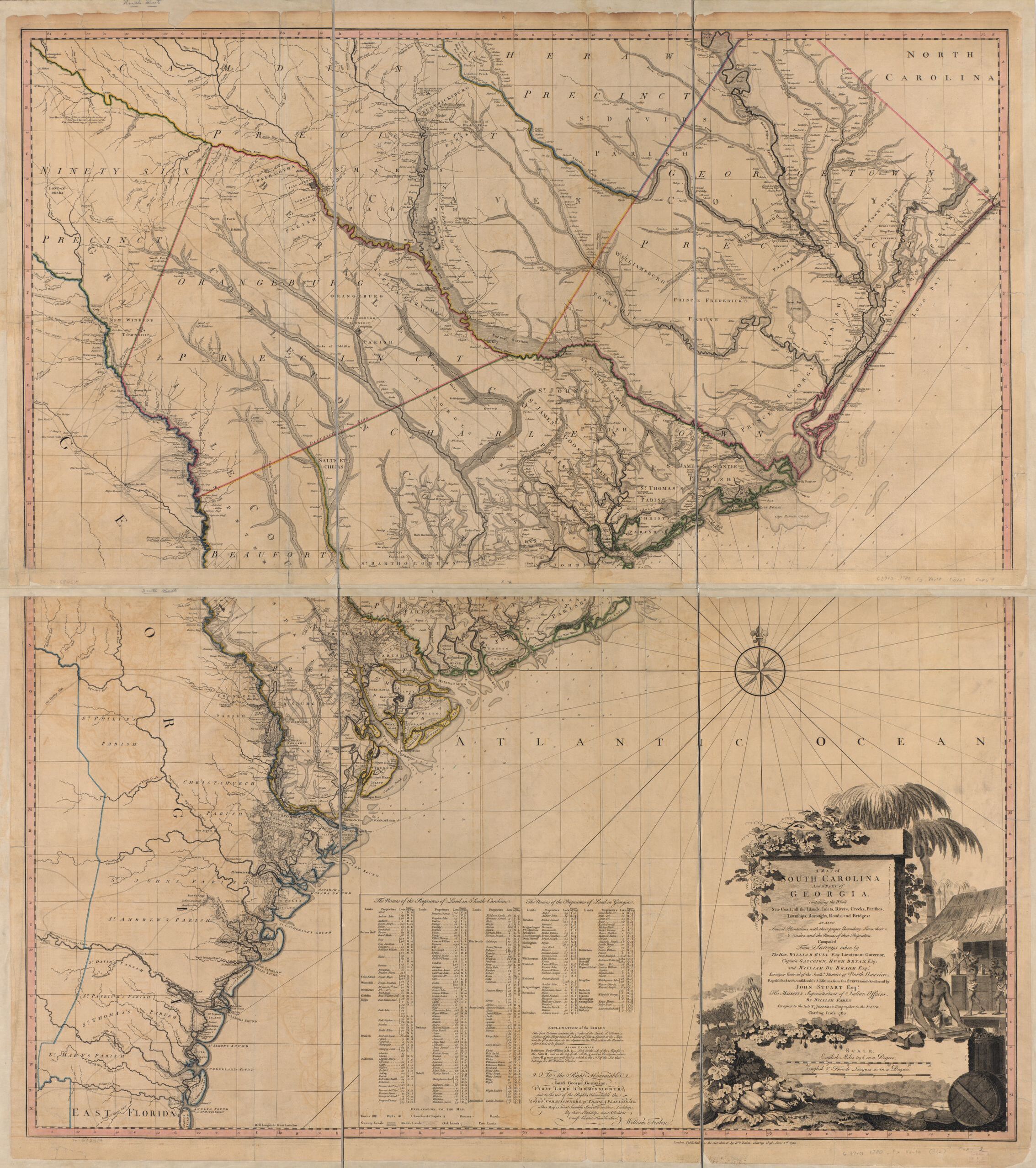

Indigo is the name of a large family of deciduous shrubs, identified in modern scientific nomenclature as part of the genus Indigofera. This genus encompasses many hundreds of species of indigo, most of which flourish in tropical areas like India, Africa, and Latin America. Some species are native to subtropical climates, however, and flourish in places like the coastal regions of the American southeast.

Indigo is also the name of an organic blue dye extracted from the leaves a number of plants around the world. For many thousands of years, humans have used this dye to impart a lasting blue color to a wide variety of textiles. From the humble vestments of blue-collar laborers, to royal robes, to tapestries and other artistic expressions, indigo is deeply imbedded in the long history of human culture.

Botanical historians believe that ancient people on the subcontinent of India were the first to domesticate a plant now identified by the scientific name Indigofera tinctoria. The deep blue dye they extracted from its leaves was dried into a powder or small cakes and exported to the east and to the west. Two thousand years ago, the Romans called this product indicum, and that name formed the root of the later English spellings, indico and indigo.

Early trade routes like the Silk Road brought indicum to Medieval Europe, but professional trade guilds actively resisted the introduction of Indian indigo into Europe for many generations. Since ancient times, Europeans had cultivated the woad plant (Isatis tinctoria) to produce a very similar blue dye for textiles, and woad farmers and dyers wanted to protect their traditional trade. As indigo production shifted to the New World colonies in the late sixteenth and early-seventeenth centuries, however, Europeans eventually discovered that indigo was cheaper and more colorfast than woad, and that traditional market declined.

What does indigo have to do with South Carolina history?

Indigo was grown in early South Carolina to produce blue dye that was exported to England for use in the British textile industry. Indigo formed a significant part of the South Carolina economy for approximately fifty years, from the late 1740s to the late 1790s. During that period, indigo (or, more specifically, indigo dyestuff) was South Carolina’s second most valuable export, behind rice.

The cultivation and production of indigo also involved the labor of thousands—perhaps tens of thousands—of people in the South Carolina Lowcountry. For this reason, the cultural memory of indigo is heightened among members of the African-American community along what is now called the Gullah Geechee Cultural Heritage Corridor of South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida.

Why was indigo cultivated in South Carolina?

Early South Carolina planters cultivated indigo to satisfy commercial demand for the dye product in the English (later British) textile industry. This activity was one small part of a much larger mercantile economy. From a mercantile perspective, the entire purpose of the Carolina colony was to produce resources and wealth that would enhance the larger British economy and support the expansion of the British empire. The cultivation of indigo in colonial South Carolina was but a cog in that macroeconomic wheel of fortune that revolved around the hub of London.

Early South Carolina planters cultivated indigo to satisfy commercial demand for the dye product in the English (later British) textile industry. This activity was one small part of a much larger mercantile economy. From a mercantile perspective, the entire purpose of the Carolina colony was to produce resources and wealth that would enhance the larger British economy and support the expansion of the British empire. The cultivation of indigo in colonial South Carolina was but a cog in that macroeconomic wheel of fortune that revolved around the hub of London.

As with tobacco in Virginia and sugar cane in the Caribbean, indigo was quite literally a foreign commodity to the early settlers of South Carolina. They did not plant indigo here as an extension of farming traditions back “home.” Textile merchants in eighteenth-century England were certainly familiar with indigo dye, but English farmers had no history of cultivating indigo as a crop. For South Carolinians, the foray into indigo production was a purely speculative venture.

Indigo had no value to the early settlers of South Carolina except as a commodity for export. As a plant, one couldn’t eat it, smoke it, feed it to animals, make it into clothing, or build a house out of it. The process of extracting the dyestuff from the plant was costly, time consuming, and labor intensive. The only motivation for investing time, money, and resources into such undertaking was the promise of profit at a market located more than three thousand miles away. Some of South Carolina’s indigo might have been used to dye textiles locally, but, prior to the nineteenth century, we purchased the vast majority of our textiles directly from England, “dyed in the wool.”

Which species of Indigo were cultivated in early South Carolina?

Three distinct species of indigo were cultivated during the first century of the colony of South Carolina. The first and most logical variety is, of course, the native species of wild indigo now classified as Indigofera caroliniana. This is a subtropical species that is found from southern Virginia to Louisiana along the eastern seaboard and Gulf Coast of North America. Colonists did experiment with it here in the eighteenth century, but they deemed its dyestuff to be inferior—in both color and volume—to that of two imported species.

The ancient Indian species (Indigofera tinctoria) came to early South Carolina through contact with English, French, and Dutch merchants trading across the Atlantic and throughout the Caribbean. Because many French planters cultivated this Indian species in their Caribbean colonies, such as Saint-Domingue (Haiti) on the island of Hispañola, eighteenth-century South Carolinians usually referred to this species as “French” or “Hispañola” indigo.

A species of indigo native to Guatemala (Indigofera suffruticosa) also came to early South Carolina through trans-Atlantic and Caribbean trade networks. This Latin American species was cultivated for centuries by the indigenous Maya people of that region, and Spanish colonists began exporting indigo dye from Guatemala to Europe in the 1550s. Thanks to English trade with Spanish and Dutch merchants in the Caribbean, the seeds of Indigofera suffruticosa were available in eighteenth-century South Carolina, where it was usually called “Guatemala” or “Bahama” indigo. Because of its hardy nature and beautiful dye, this Latin American species became the principal species of commercial indigo cultivation in South Carolina.

Bromo indigo; Vat bromo-indigo; C.I.Vat blue 5;

When did indigo cultivation begin in South Carolina?

Indigo seeds (either I. tinctoria or I. suffruticosa) came to South Carolina with the first English settlers in 1670, along with the seeds of a variety of other plants. In the early decades of this colony, European settlers planted a number of different crops as they tried to learn the qualities of the local soils and the seasonal ranges of the climate. The same process of crop experimentation had led the early settlers of Virginia to focus on tobacco. The early English settlers of Barbados, Antigua, and Jamaica had also experimented with indigo as well as tobacco, ginger, sugar cane, and cotton. Once those Caribbean planters perfected their techniques of harvesting sugar and rum from sugar cane in the 1650s, however, they quickly abandoned their experiments and focused on that most profitable plant. Similarly, when South Carolina planters perfected the cultivation of rice in the late 1690s, they temporarily set aside other crops like indigo and focused on the most profitable commodity.

The French Protestant (or Huguenot) immigrants who came to early South Carolina probably arrived with a greater familiarity with indigo than their English neighbors. Because of France’s traditional commercial ties with Spain, and France’s colonies in the Caribbean, it’s likely that some of the Huguenot settlers who established plantations in the Carolina Lowcountry, especially around Santee River delta, in the early 1700s might have been cultivating indigo for their own use.

The French Protestant (or Huguenot) immigrants who came to early South Carolina probably arrived with a greater familiarity with indigo than their English neighbors. Because of France’s traditional commercial ties with Spain, and France’s colonies in the Caribbean, it’s likely that some of the Huguenot settlers who established plantations in the Carolina Lowcountry, especially around Santee River delta, in the early 1700s might have been cultivating indigo for their own use.

White Europeans were not the only people living in the Lowcountry of South Carolina, of course, so the story of indigo in this colony involves many other people. To my knowledge, there is no surviving evidence that the indigenous Native Americans of early South Carolina cultivated indigo, so the local Indians could not have introduced it to the early settlers, as they did with maize and tobacco elsewhere.

It is possible, however, that African captives transported to early South Carolina might have had some experience with indigo cultivation in their native land, or had learned about it in the Caribbean before coming here. Enslaved people were certainly deeply involved in the production of indigo in early South Carolina, but it seems unlikely that they would have had the freedom to cultivate the crop and manufacture the blue dye for their own use.

There is very little surviving evidence of the cultivation and production of indigo in the early years of eighteenth-century South Carolina, but it’s certain that some people were growing it here. An early South Carolina planter named Robert Stevens (died 1720), for example, described the process of extracting the blue dye from the plant in the autumn of 1706. The eye-witness observations of “Allegator” Stevens, as he was apparently known, were later reprinted on the front page of the South Carolina Gazette on April 1st, 1745.[1]

How did indigo become a major crop in South Carolina?

The large-scale, commercial exportation of indigo dyestuff from South Carolina to England commenced in 1747, following a revival of interest in the crop. The principal motivation behind this revival was an economic decline caused by a decade of war with Spain and France (the “War of Jenkins’ Ear” and “King George’s War,” 1739–48). Because much of this warfare unfolded on the waters of the Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, the complex web of colonial trade networks suffered greatly. South Carolina planters who had focused almost solely on rice, for example, saw their profits fall while insurance rates skyrocketed. At the same time, Britain experienced great difficulty in obtaining exotic goods like indigo, olive oil, silk, and wine through their traditional suppliers, France and Spain. In light of these conditions, the governments of both Britain and her American colonies encouraged immediate diversification.

During the late 1730s and early 1740s, hundreds of South Carolina planters experimented with a variety of plants in the hopes of finding new commodities that were both well-adapted to the local soil and climate and valuable to the British economy. In May of 1744, the South Carolina legislature enacted a stimulus package to “grow” the local agricultural economy. To encourage planters to experiment with the production of wine, olive or sesamum oil (see Episode No. 78), flax, hemp, wheat, barley, cotton, indigo, and ginger, the provincial government offered a cash bounty of one shilling (South Carolina currency) per pound of merchantable produce for export.[2]

The bounty enacted in 1744 was to be in effect for a period of five years, but the fast pace of agricultural experimentation led to an important revision in less than two. Benne seed oil and indigo were the front runners in this competition, but indigo was clearly in the lead. In mid-April 1746, the South Carolina legislature cancelled the bounty on indigo only, stating that so much of the blue dye had been produced recently that the continuation of the bounty was impractical.[3]

The economic drive to produce indigo was further enhanced in the spring of 1748 when the British Parliament enacted their own stimulus package. South Carolina merchant James Crokatt, who had returned to England, successfully lobbied the government to offer a bounty (initially six pence sterling per pound) to the British purchasers of American indigo. That cash incentive, which took effect in 1749, convinced most South Carolina planters to cease experimenting with other crops and to focus on indigo.

But indigo was always a secondary crop. When Britain’s war with France and Spain ended in late 1748, the price of rice quickly improved and continued to be South Carolina’s primary export. Indigo production slowed dramatically after the war, however, and didn’t rebound until Britain again declared war on France in the mid-1750s. From that point onward, South Carolina’s indigo exports increased rather steadily over the next twenty years.

-

The Timeless Art of Denim Indigo Dye

NewsJul.01,2025

-

The Rise of Sulfur Dyed Denim

NewsJul.01,2025

-

The Rich Revival of the Best Indigo Dye

NewsJul.01,2025

-

The Enduring Strength of Sulphur Black

NewsJul.01,2025

-

The Ancient Art of Chinese Indigo Dye

NewsJul.01,2025

-

Industry Power of Indigo

NewsJul.01,2025

-

Black Sulfur is Leading the Next Wave

NewsJul.01,2025

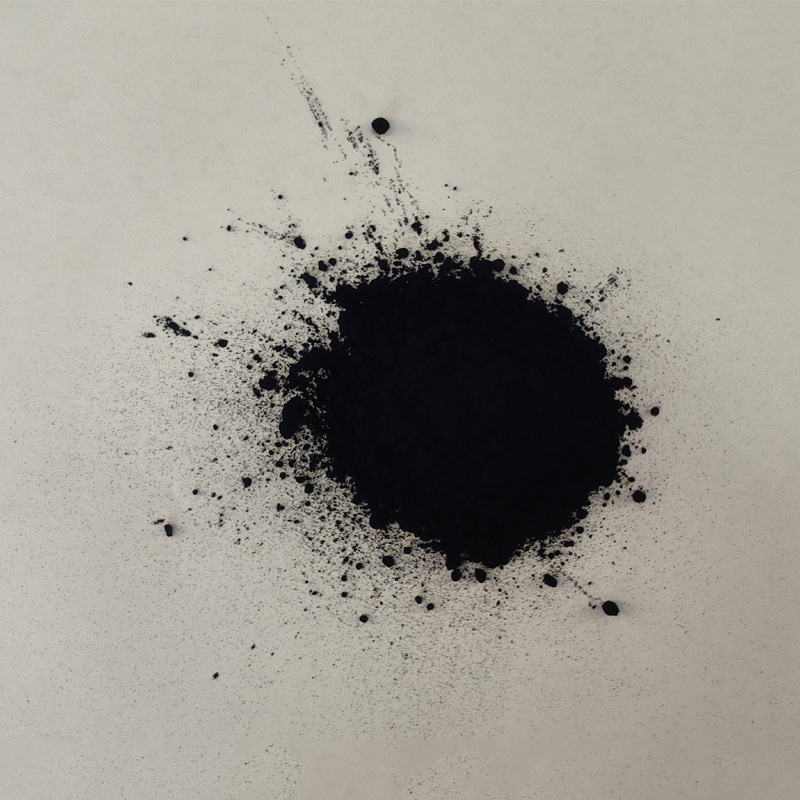

Sulphur Black

1.Name: sulphur black; Sulfur Black; Sulphur Black 1;

2.Structure formula:

3.Molecule formula: C6H4N2O5

4.CAS No.: 1326-82-5

5.HS code: 32041911

6.Product specification:Appearance:black phosphorus flakes; black liquid

Bromo Indigo; Vat Bromo-Indigo; C.I.Vat Blue 5

1.Name: Bromo indigo; Vat bromo-indigo; C.I.Vat blue 5;

2.Structure formula:

3.Molecule formula: C16H6Br4N2O2

4.CAS No.: 2475-31-2

5.HS code: 3204151000 6.Major usage and instruction: Be mainly used to dye cotton fabrics.

Indigo Blue Vat Blue

1.Name: indigo blue,vat blue 1,

2.Structure formula:

3.Molecule formula: C16H10N2O2

4.. CAS No.: 482-89-3

5.Molecule weight: 262.62

6.HS code: 3204151000

7.Major usage and instruction: Be mainly used to dye cotton fabrics.