A Comprehensive Guide To Getting Started With Indigo Dyeing

As a denim enthusiast, what really attracted me to jeans was not only the cool image associated with them. It was the appreciation for the dark blue colour of a new pair of jeans, and how that colour changes and evolves with wear.

It’s through denim that I became acquainted with indigo—something that has become a hobby of mine in its own right. I think every denimhead dreams of making their own jeans and for me, this included making the fabric too. It is through this interest that I got acquainted with indigo as a dye, and fell in love with the Japanese technique of shibori.

Visit our buying guides before your next purchase. We guide you to the best raw selvedge jeans, denim jackets, heavy flannels, T-shirts, denim shirts, and more.

My own adventure with indigo dyeing began when I took a course hosted by Douglas Luhanko and Kerstin Neumüller, who run Second Sunrise in Stockholm, and who have incidentally written a very good book about indigo dyeing.

indigo blue vat blue

I’ve put together this guide using the knowledge that I acquired from experts Kerstin and Douglas, along with things I’ve picked up from my own experimentation in my backyard.

In this guide, I’ll cover the following:

- What is indigo and where does it come from

- Preparing your indigo dye bath

- Preparing your fabric, or garment, for dyeing and a basic shibori technique

NOTE!

If you’re intending to use this article as a guide for your indigo dyeing, please read through all sections before starting. It’s best to have everything prepared before you start!

PART I | Indigo: What It Is and Where It Comes From

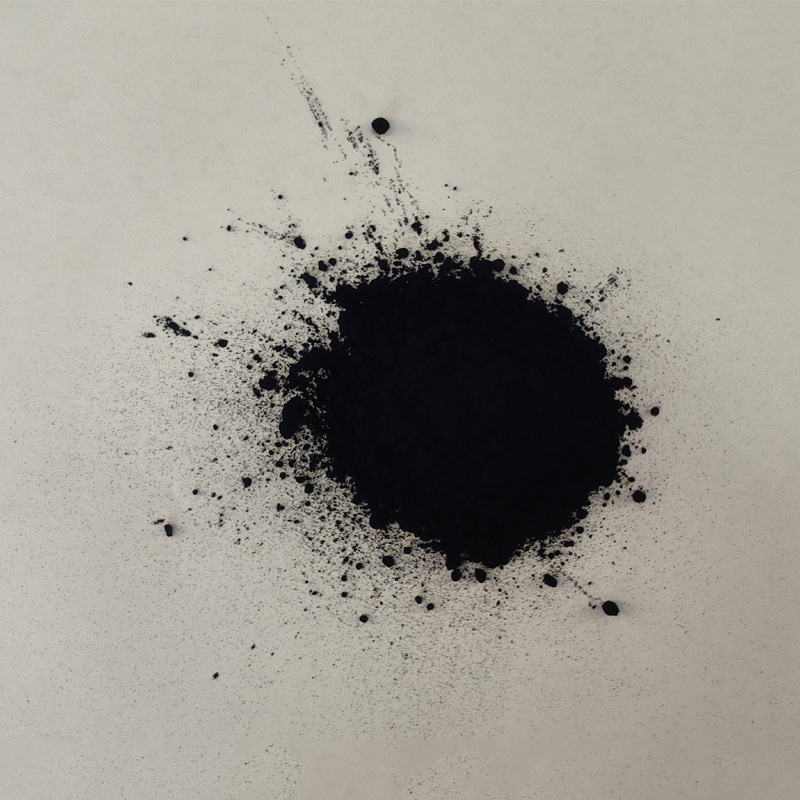

When you’re working with indigo as a dye, you’ll usually encounter it in a stabilised, raw form in bricks or powder from which you create your dye mixture.

For now, I’ll keep it simple, but understanding where indigo comes from and how it is used to dye with is a subject that we could write an entire member resource on. Oh wait, we did!

Indigo nowadays comes in two forms: plant-based natural indigo and a synthetic indigo, both of which I’ll talk about below.

Natural Indigo

Indigo dye is derived from several plant species across the world, but most significantly from the Indigofera genus of plants from the legume family (that’s peas to you and me) that grow naturally in the temperate to tropical climates of Asia and Africa.

The most significant plant of this family is Indigofera tinctoria—the one below—which yields the highest concentrations of indigo pigment and thus gives the deepest shades of indigo when used in dyeing.

Other species of Indigofera, such as Indigofera suffruticosa, can and have been used to extract indigo for dyeing. But today, most natural indigo sold for dyeing come from Indigofera tinctoria due to the richness of the dye it produces.

You might come across ‘European indigo’ in the marketplace, but be aware that whilst what you’re buying is indigo dye, it has been extracted from the unrelated Isatis tinctoria (below), or woad as it’s better known, which is more suited to the northern climates and has a huge natural range, from North America, to Scandinavia, to the Siberian steppe.

Woad yields a much lower concentration of indigo dye compared to Indigofera tinctoria and as a result, it gives much lighter shades.

Synthetic Indigo

More commonly today, synthetic indigo is used to dye clothing on an industrial scale due to its easier extraction and abundance of raw material.

Indigo was first synthesised by German chemist Adolf von Baeyer in 1878 from isatin but the synthesis of indigo remained impractical until Johannes Pfleger and Karl Heumann developed a mass production synthesis for BASF, from coal tar. This commercially feasible manufacturing process that was in use by 1897.

Interestingly enough, whilst both natural and synthetic indigo are chemically identical, many people attest to a difference in how they fade.

The Difference Between Natural and Synthetic Indigo

Synthetic indigo has a tendency to create higher contrast fading on jeans, whereas jeans dyed with natural indigo lean towards offering a more equalised vintage fade.

The reason behind this still remains unclear although it should be noted that synthesised indigo is supplied at a 99.9% purity, whereas natural indigo has a purity of roughly 50%. Many people suspect that it is the other natural compounds within natural indigo dye that contribute to the difference in how the dye fades on fabric.

Whichever dye you choose to use to dye with, the process for creating your dye mixture is the same. As synthetic indigo has a much higher percentage of indigo per weight than the natural form, you only need to use one-quarter the amount of synthetic indigo. Indigo in powdered form is one of the easiest forms, as the bricks must be ground to a powder before use.

Let’s get started dyeing! The first step is preparing your dye bath which, when it comes to indigo, is done through a careful process …

PART II | Preparing Your Dye Bath

Unlike some other pigments, the process of dyeing with indigo can be somewhat complicated.

Maybe you’ve re-dyed your black jeans with for instance Dylon dye in the washing machine? Dyeing with indigo is nothing like that. If you throw your indigo powder in the washing machine along with your fabric, you will not get that deep-blue hue you’re after.

That’s because the indigo dye you buy is in a stable, oxidised form (called indigotin), which is not water soluble, meaning it will not bind well to the fabric you’re going to dye.

What you’re going to have to do is make the indigo dye soluble as well as deoxygenate it.

Preparing the Dye

The quantities of each ingredient you’ll need to create your dye will vary depending on the size of the bath you want to create and the concentration of the indigo solution with which you’ll be dyeing.

For this guide, I’ll use natural indigo so make sure to adjust the quantity of indigo if using the synthetic version. Again, no real difference between whether you choose natural or synthetic indigo: I’ve chosen natural as I can buy it easily at a local handicraft shop.

You’ll need:

- A tub large enough to hold 8 litres of dye solution. A 12-litre tub is a good size to allow some room to work with and make sure you don’t spill a lot of the solution

- Rubber gloves! The solution is very alkaline and can irritate skin

- Two 1-litre jars or jugs. Preferably with a lid

- A stirring implement, which can be made of wood or metal, but should ideally reach to the bottom of the bath

- 2 or 3 buckets filled with clean water for rinsing your dyed fabrics. The last bucket should contain a half cup of vinegar

- Litmus strips for testing the pH level of your dye bath

- A clothes line or clothes horse to hang your dyed fabric on afterwards

- 25g natural indigo powder

- 25g/31ml of ethyl alcohol or methylated spirits (you can buy this from your pharmacy!)

- 25g soda ash (sodium carbonate)

- 25g sodium dithionite

PRO TIP!

Make sure you have all your materials and tools ready before going any further. Realising half way that you’ve forgotten an ingredient will ruin your dye solution!

Gotten this far? Great! Now we can start making your indigo stock solution, which is a concentrated form that will be added to the main volume of water later

Step 1: Reduce the Indigo Powder

The first step is to solubilise the indigo powder (or “reduce” it, as it’s technically known).

Pour your indigo powder into one of the 1-litre jars and add the ethyl alcohol or methylated spirits. Mix with a spoon or stirring implement until it forms an even paste.

We’ll call this Jar A.

Step 2: Create a Salt Solution

In your second 1-litre jar, add 300ml of water at 50°c. If you haven’t got a thermometer, make sure it’s warmer than the temperature you’d take a shower at.

To this water you’ll add 25g of soda ash (sodium carbonate) and 25g of sodium dithionite. Gently stir the salts in to disperse them into the water.

Really, do this gently as you want to avoid introducing air into the solution!

This one, we’ll call Jar B.

IMPORTANT!

- Always add the soda ash and sodium dithionite into the water. Never pour the water onto the soda ash or sodium dithionite!

- Always wear gloves and if possible, protective eyewear as soda ash is highly alkaline and will irritate if it comes into contact with your skin and eyes.

You’ll want to use your litmus strip now to check the pH level of the salt solution. Ideally, it has a pH of 11 to 13, which is highly alkaline.

Close the jar with a lid to preserve the heat and let the solution stand for ~10 mins, allowing the salts to dissolve fully into the water.

Step 3: Mix the Reduced Indigo With the Salt Solution

Now you’re going to slowly add the salt solution from Jar B to the indigo solution in Jar A.

You’ll want to make sure that both solutions mix well in order to reduce or deoxygenate, as much of the indigo as possible.

Do this by stirring very gently, avoid any splashing or lifting your stirring implement out of the solution. Again, this is because you want to avoid introducing any oxygen into your dye solution!

Leave your combined indigo solution covered for another 30 minutes to let it completely reduce. By this point, your dyeing solution should have the colour of pea soup, i.e. greenish yellow.

If it looks a rich, dark blue then you’ve oxygenated the mix too much! You’ll need to add more sodium dithionite into your solution and stir gently again to remove the oxygen!

Step 4: Prepare the Dye Bath

You’re ready to prepare your dye bath!

Fill your large bucket in which you’ll be dyeing with 8-10 litres of warm water. You’ll need to factor in the weight of the fabric here and how much liquid it will displace when immersed in your dye bath.

To further ensure that the indigo solution you’ll be diluting into your dye bath is deoxygenated, add 5 grammes of sodium dithionite and 2 grammes of soda ash for every 1 litre of water used in your bath.

Step 5: Add the Indigo Solution

Introduce your reduced indigo solution into the dye bath!

Again, you’ll want to do this whilst minimising the amount of oxygen introduced into the bath. I’ve done this by immersing the entire jar of reduced solution into the bath (with a gloved hand!) and allowing the solution to disperse into the dye bath.

Some people advise against introducing the sediment that might have formed on the bottom, but I’ve found this difficult to do without further oxygenating the dye bath. The sediment is simply indigo that hasn’t become soluble and I’ve never found that the sediment, which sinks to the bottom, has interfered with the results of the dyeing.

You’re ready to dye!

Ideally, you’ll have your fabric ready to dye by the time your dye bath is ready to use. If not, try and cover it or seal the bath until you’re ready to use it.

Now let’s take a look at some dyeing techniques!

-

The Timeless Art of Denim Indigo Dye

NewsJul.01,2025

-

The Rise of Sulfur Dyed Denim

NewsJul.01,2025

-

The Rich Revival of the Best Indigo Dye

NewsJul.01,2025

-

The Enduring Strength of Sulphur Black

NewsJul.01,2025

-

The Ancient Art of Chinese Indigo Dye

NewsJul.01,2025

-

Industry Power of Indigo

NewsJul.01,2025

-

Black Sulfur is Leading the Next Wave

NewsJul.01,2025

Sulphur Black

1.Name: sulphur black; Sulfur Black; Sulphur Black 1;

2.Structure formula:

3.Molecule formula: C6H4N2O5

4.CAS No.: 1326-82-5

5.HS code: 32041911

6.Product specification:Appearance:black phosphorus flakes; black liquid

Bromo Indigo; Vat Bromo-Indigo; C.I.Vat Blue 5

1.Name: Bromo indigo; Vat bromo-indigo; C.I.Vat blue 5;

2.Structure formula:

3.Molecule formula: C16H6Br4N2O2

4.CAS No.: 2475-31-2

5.HS code: 3204151000 6.Major usage and instruction: Be mainly used to dye cotton fabrics.

Indigo Blue Vat Blue

1.Name: indigo blue,vat blue 1,

2.Structure formula:

3.Molecule formula: C16H10N2O2

4.. CAS No.: 482-89-3

5.Molecule weight: 262.62

6.HS code: 3204151000

7.Major usage and instruction: Be mainly used to dye cotton fabrics.