INDIGO IS AN ORGANIC PIGMENT THAT CAN BE GROWN IN PLANTS

Indigo pigment is produced within the leaves of a broad range of plants across an array of genera. They have been historically grown on different parts of the earth that suit their particular needs (sun, moisture, soil, etc). Varieties range from Indigofera Suffruticosa in Central America, Persicaria Tinctoria in Asia, Isatis Tinctoria throughout Northern Europe and Indigofera Tinctoria primarily in South and Southeast Asia. I grow and have extra seed for each of these varieties, please get in touch if you are interested in growing any of them. You can certainly find a variety that you could grow in your local climate.

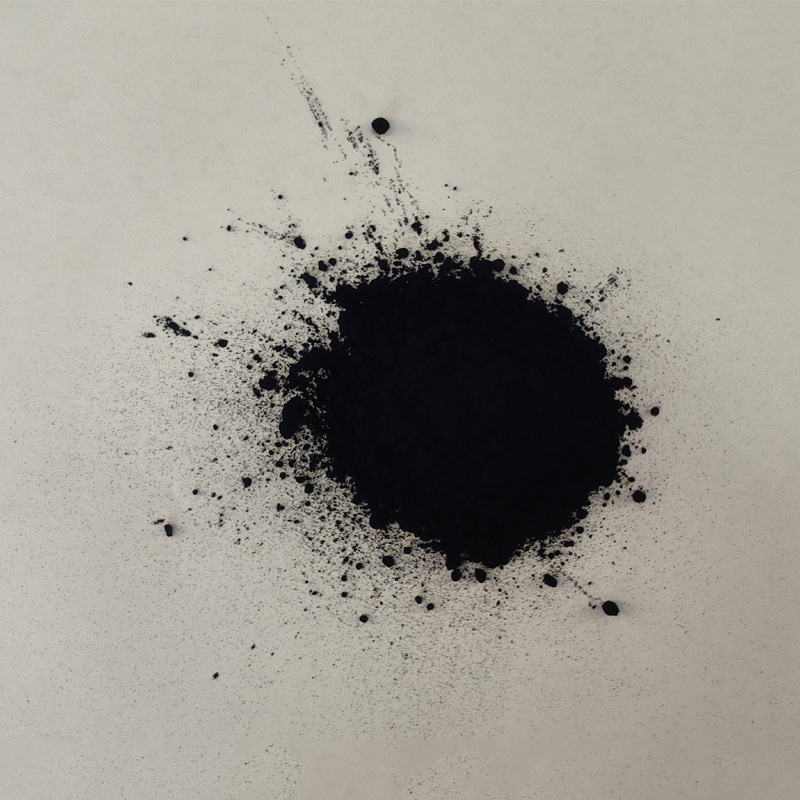

These plants each contain only a small percentage by weight of actual dyestuff in their leaves. It can take tons of plant material to make a few pounds of dyestuff. One way or another, the pigment is extracted from the leaves and can be purchased in a concentrated pasted, dried powder, ball or brick form. This indigo concentrate is often graded on its Indigotin content level, the percentage by weight of actual pigment. Indigotin levels of quality dye concentrate almost always range between 10% and 50%.

indigo blue vat blue

The indigo pigment molecule is non-reactive in water. It cannot be dissolved (like salt for example), but it can and must be put into liquid suspension as a first step to making an Indigo vat. The majority of indigo extract in the market is synthetically produced from fossil fuel extracts, it is generally cheaper, though functionally nearly identical to indigo derived directly from plants. The most common form of natural indigo in the marketplace is concentrated pigment in finely ground powder form from the plant Indigofera tinctoria or related species. All processes that I'm describing here presume that is the dye product you're working with. There are a wealth of other indigos out there, both natural and synthetic, most all of which you can treat similarly to this and get good results.

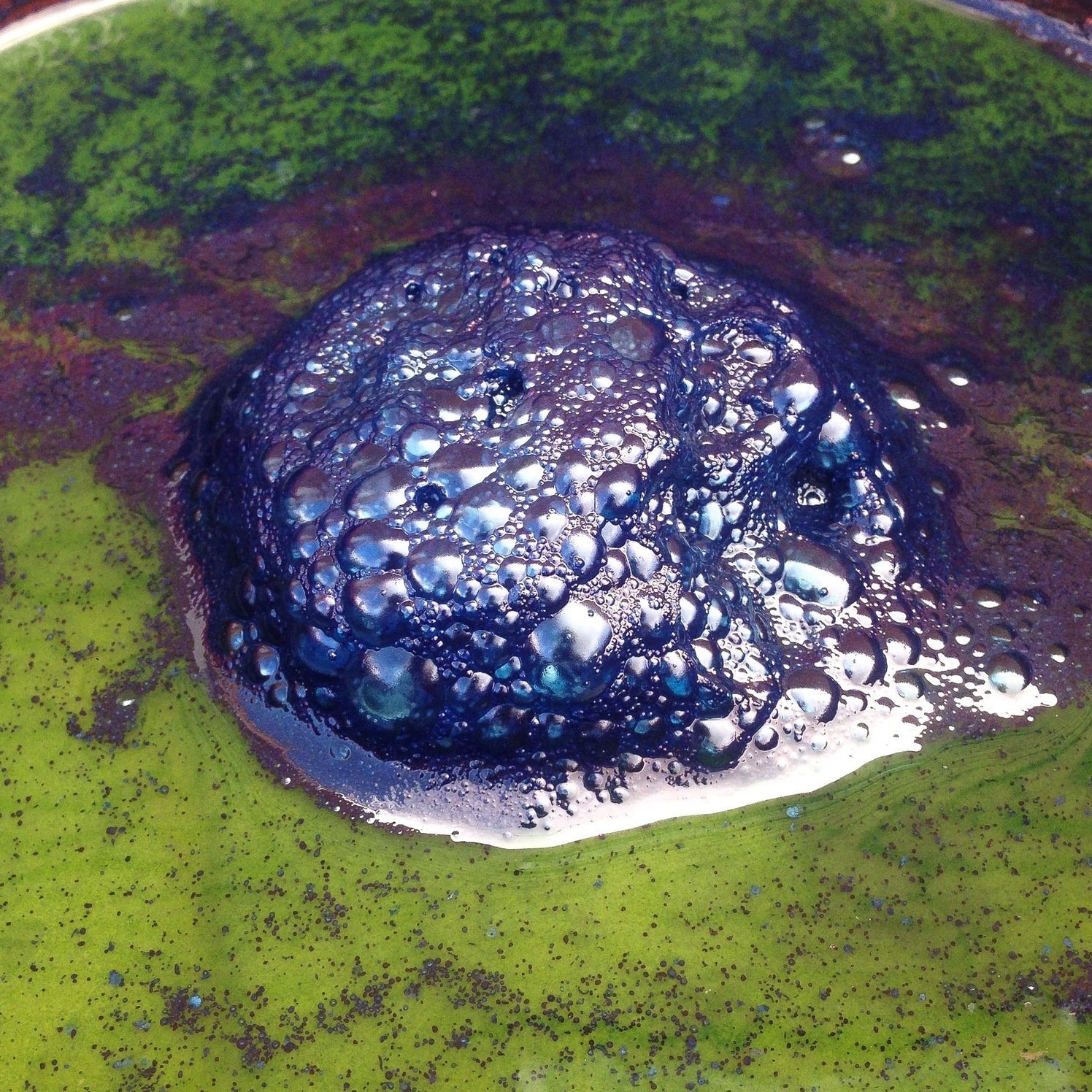

The indigo pigment molecule, as purchased, will not react with cloth or dye it. It can be rubbed in and will cause a temporary stain, but it is not dye. For the indigo to actually transfer and adhere with the cloth, we must create what is called a Vat. The Vat will be referred to with a capital V here, for at the scale of the individual dyer, the entity known as the Vat has an incredible amount of history and personage, requires pampering and sustenance, often warmth and food. The Vat serves to modify the Indigo molecule in such a way that it eschews inertness (as it tends to be when in blue-powder form) and chemically interacts with AKA dyes cloth (and other things, but for our purpose, cloth). The Vat must fulfill two conditions to properly modify the Indigo. The Vat must first have an elevated pH, a condition know as alkalinity in which the amount of OH− ions exceeds that of H+ ions in the solution. Second, the Vat must be a reduced solution, meaning (in this case specifically) that the solution is devoid of dissolved oxygen and there are an excess of electrons in solution which causes the oxygen atoms present on the indigo molecule to be reduced (essentially snatching up these electrons into their orbit) and changing the Indigo molecule into what is called Leuco-Indigo which becomes dissolved in the Vat solution. This change is easily visually confirmed! Leuco-Indigo will appear as a transparent yellow-green (not too dissimilar from a childhood favorite soda, Mountain Dew) as compared to the opaque dark blue of Indigotin in suspension.

This photograph displays the indigo molecule in multiple forms. The dark, opaque blue ‘flower’ that sits atop an indigo vat is oxidized indigo - a molecule that will not dye fabric. The leuco-indigo dissolved in the Vat is visible as a yellow-green liquid - this molecule has the ability to chemically bond to (dye!) many different materials.

Once we have a properly reduced, leuco-indigo rich Vat, we can dip our cloth to dye with indigo. At the moment that the cloth emerges from the Vat it will be colored a tinge of green with the reduced leuco-indigo. As the piece comes into contact with the atmosphere, the pigment molecule, now adhered to the fabric, will lose its excess electrons and visibly transition back to blue.

There are many different ways of creating a Vat! There are many paths that will get you to the same finished product, a beautifully dyed blue piece! Each Vat style requires different ingredients and maintenance, and each has a set of positive and negative attributes.

The single best source for information about different styles of indigo and different ways of producing a vat is this book by John Marshall

The simple recipe that I advocate for the beginner is one that fits with our modern world. It is easy to make, requires no upkeep and (if properly sealed between uses) can be used on-demand for months at a time until it is exhausted of pigment. It is know as The Iron Vat. I've outlined the pros and cons for working with the Iron Vat below. If you have questions about this or any other kind of vat, feel free to get in touch.