Marbling With Indigo

Many of us natural dyers are well familiar with the process of concocting an indigo vat and the working properties of indigo as a dye. It is truly remarkable that so many historical cultures throughout the world developed a practical understanding of the complex chemistry governing the indigo vat, leaving us with a wealth of cultural and artistic heritage centered on this beautiful dye. But indigotin, the indigo blue which colors fibers dyed in the indigo vat, is an insoluble organic compound and can be used as a pigment. It may be mixed with a binder for use as paint without going through the trouble of making an indigo vat or a lake pigment. Let's review the process by which indigo is made:

-

Indigo precursors naturally occur in the leaves of an indigo-bearing plant. After harvesting, these precursors are converted by enzymatic hydrolysis to indoxyl.

-

When oxidized, two indoxyl molecules join with oxygen to form indigotin.

-

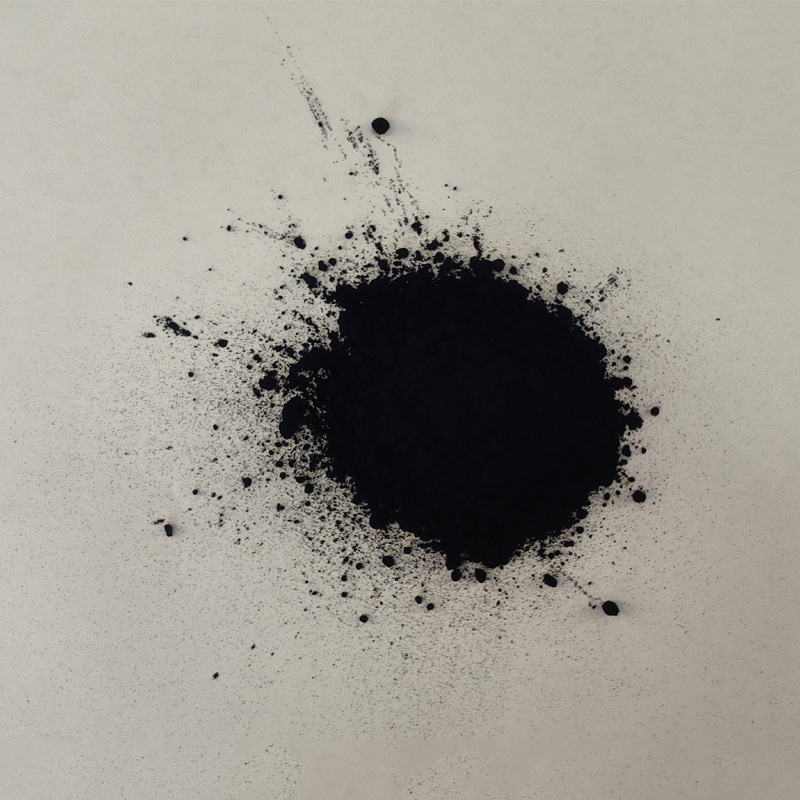

Indigotin is indigo blue! Indigotin is insoluble, and can be used as a rich navy blue pigment.

-

Natural dyers now mix up their indigo vats to reverse the process. To work as a dye, an antioxidant reduces indigotin to leuco-indigo suspended in water. Fibers lowered into the vat become saturated with leuco-indigo, which spontaneously oxidizes to indigotin when lifted from the vat and exposed to air.

It's quite the feat of chemistry, but the peculiar dual nature of indigo provides its distinction as an artists' material. Used as a dye, indigo's working qualities have inspired resist techniques in cultures around the world. After dyeing, the indigo is not chemically bound to fabric and can be abraded from it with washing and wearing, giving us the particular worn-in look of denim. And because indigo is quite when oxidized, it has better lightfastness that other natural dyes.

Sources of indigo pigment

In medieval Europe, indigo was prepared as a pigment by skimming and drying the flower from the surface of a woad vat, called blue florie, or grinding white lead with imported indigo. Indigo was widely available, fairly inexpensive, and in common use as a workaday blue pigment. It is a strongly tinting, dark, and slightly greenish shade of blue. Indigo is certainly a regal dye, one of the few lightfast historical grand teints. But as a pigment, its lightfastness did not match the more permanent and expensive mineral blues.

For use as a pigment today, pure indigo can be finely ground and mixed as watercolor, tempera, or oil paint. If you're a dyer, you can use the botanical indigo powder you already have on hand. You can also purchase the genuine botanical pigment from Kremer, from Cornellisen in the UK, or you can buy Genuine Indigo paint pre-made by a reputable paint manufacturer.

Synthetic indigo was formulated in the late nineteenth century and is chemically identical to indigotin. Slight color variations between synthetic and botanical indigo are due to additional organic compounds extracted from different species of indigo bearing plants, including the colorant indirubin, which influence the shade of blue. Either botanical or synthetic indigo can be used as a pigment, but not indigo dye sold 'pre-reduced.'

What is Maya blue?

Maya blue, or indigo-clay blue, is an indigo derived pigment used by prehispanic Maya and Aztec artisans to color murals and ceramics. This ancient azure colored pigment is so stable and lightfast it was long thought to have a mineral origin. It is made by heating a finely ground dry mixture of indigotin and clay such as palygorskite, attapulgite, or sepiolite to 356 degrees Fahrenheit. At this temperature the indigo replaces water in the clay, forming a stable compound in which the indigo is protected from light. Once cooled, Maya blue pigment can be mixed with a binder and used in all sorts of applications. Maya blue requires a small amount of indigo, is lightfast, and is a lovely turquoise-inflected shade. I have only found Maya blue pigment available from Rublev, but it is not a difficult pigment to make at home.

How do indigo and Maya blue fare in paper marbling?

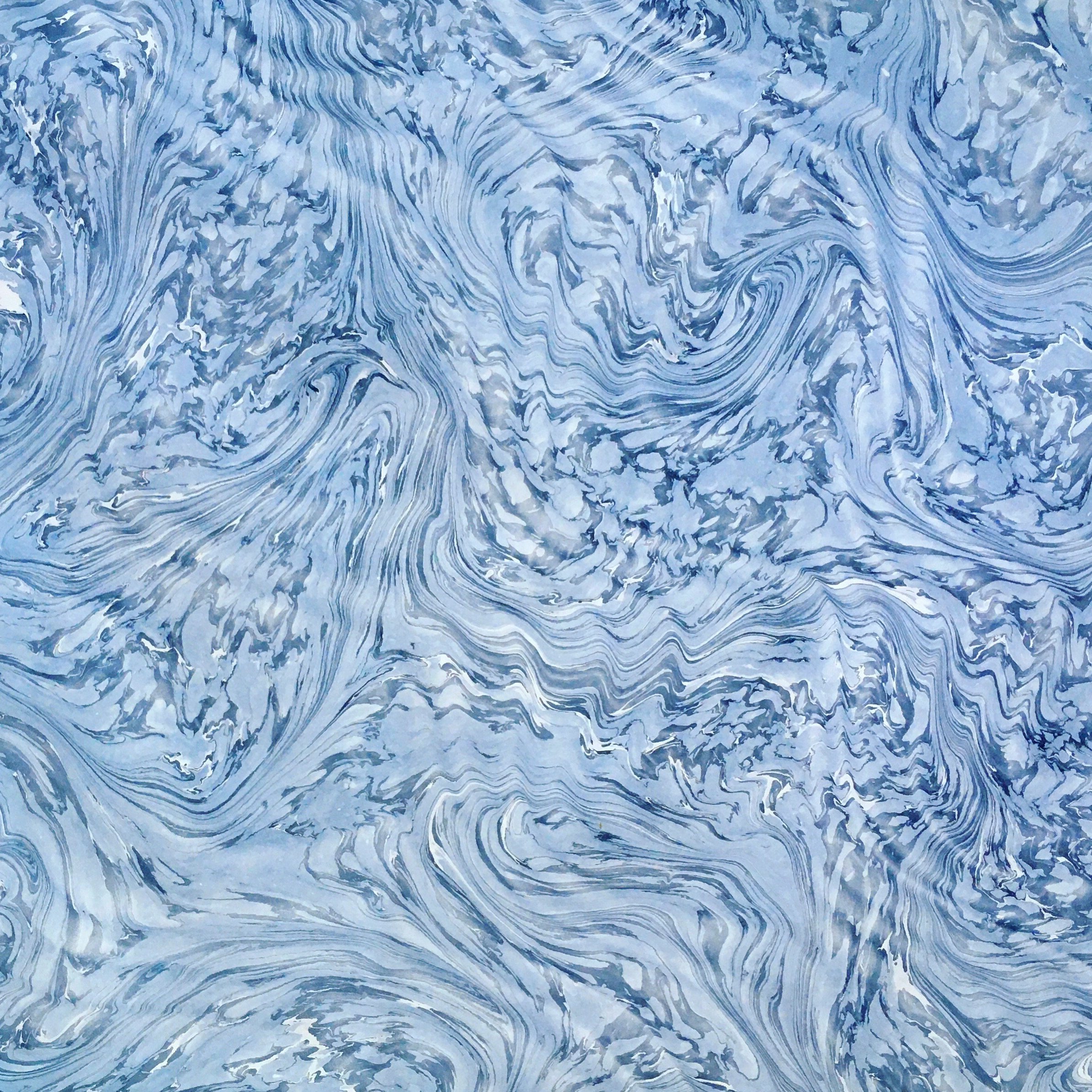

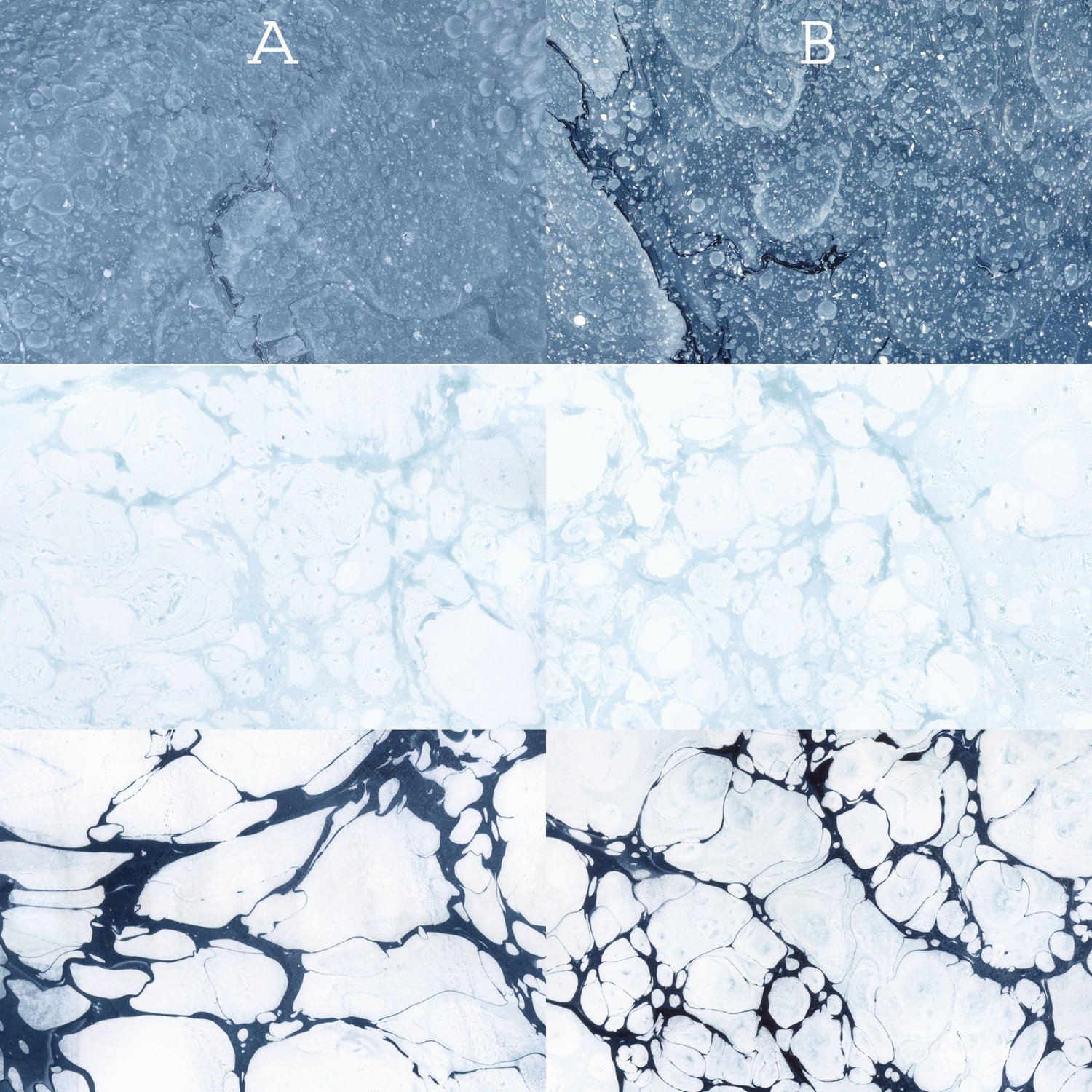

Below are the results of some preliminary marbling experiments with homemade indigo watercolor and Maya blue watercolor.

-

Top: indigo watercolor

-

Middle: Maya blue watercolor

-

Bottom: both shades of blue

-

Column A: no mordant. Quite fuzzy and streaky

-

Column B: pre-mordanted with 1.5 teaspoons aluminum sulfate/pint water

I did struggle with getting the Maya blue to behave, though it functioned well in previous trials alone and mixed with lake pigments. It is a lovely (though faint in this test), stable color which European marblers never had access to until the recipe was reverse-engineered in recent years. The pure indigo blue has a beautiful rich hue, and will be useful for mixing dark shades.

-

The Timeless Art of Denim Indigo Dye

NewsJul.01,2025

-

The Rise of Sulfur Dyed Denim

NewsJul.01,2025

-

The Rich Revival of the Best Indigo Dye

NewsJul.01,2025

-

The Enduring Strength of Sulphur Black

NewsJul.01,2025

-

The Ancient Art of Chinese Indigo Dye

NewsJul.01,2025

-

Industry Power of Indigo

NewsJul.01,2025

-

Black Sulfur is Leading the Next Wave

NewsJul.01,2025

Sulphur Black

1.Name: sulphur black; Sulfur Black; Sulphur Black 1;

2.Structure formula:

3.Molecule formula: C6H4N2O5

4.CAS No.: 1326-82-5

5.HS code: 32041911

6.Product specification:Appearance:black phosphorus flakes; black liquid

Bromo Indigo; Vat Bromo-Indigo; C.I.Vat Blue 5

1.Name: Bromo indigo; Vat bromo-indigo; C.I.Vat blue 5;

2.Structure formula:

3.Molecule formula: C16H6Br4N2O2

4.CAS No.: 2475-31-2

5.HS code: 3204151000 6.Major usage and instruction: Be mainly used to dye cotton fabrics.

Indigo Blue Vat Blue

1.Name: indigo blue,vat blue 1,

2.Structure formula:

3.Molecule formula: C16H10N2O2

4.. CAS No.: 482-89-3

5.Molecule weight: 262.62

6.HS code: 3204151000

7.Major usage and instruction: Be mainly used to dye cotton fabrics.